Tag: Camberwell Panel

..And the Sailor home from the Sea.

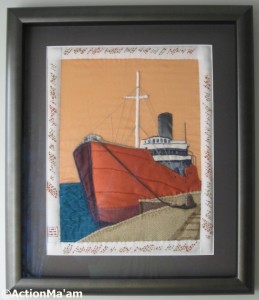

Once the Camberwell was finished, I handed the piece, still stretched on the bars I used to work it, over to my client (Action Ma’am) and her picture framer. I’m very pleased with what they came up with, so I’ve asked her to write up a little bit about framing the piece and where the Camberwell is living now.

At quite an early stage, I had decided that Camberwell was going to hang in the bathroom. An odd choice, maybe, but her colours went beautifully with the accent colours I had already chosen and the theme of nauticalia.

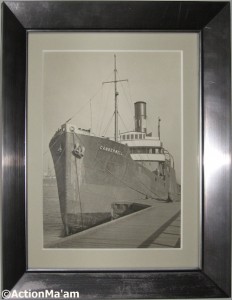

My local picture framer enthusiastically accepted the challenge of creating a suitable box-frame. We chose a rounded moulding, to echo the curve of the funnel, and charcoal for both mount and moulding to match the colour of the ribbon used for the funnel. Since it was to hang by an east-facing window, we selected a grade of conservation glass which excludes 98% of UV light. I took the opportunity to have the inspirational photo properly mounted in the frame I had bought for it from a high-street newsagent a year or so previously.

The pictures now hang either side of the bathroom door. Rachel and I had a little ceremony with sparkling white wine to hang the finished panel. I can bore for England on how wonderful it is, and admire it in comfort whilst lounging in the bath.

The title of this post is taken from RL Stevenson’s “Requiem” – text here. Or alternatively from AE Housman’s “Home Is The Sailor” (here). We both thought it was the right title, but neither of us could remember where we’d heard it, and when I Googled for it, I found myself with a positive embarrassment of riches!

The Camberwell Panel – Fourteen

So at last, Finished!

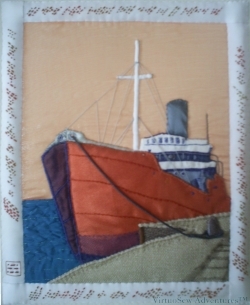

By the time I had finished stitching it all I could nearly read Morse Code, even when it was running diagonally. The dedication runs from the bottom left anticlockwise around the picture – so the top border is upside down!

When I’d finished the whole dedication, and got to the left hand border I felt the end looked a little vague, so then I worked the little cartouche at the end of the left-hand border which contains my initials in Morse code. Somehow that provided me with the “full stop” the piece needed. The dedication itself already included the date, so I only had to sign it.

My cousin has had it beautifully mounted and framed in a box frame, and I gloat over it every time I visit her. Fortunately she loves it too, and she is going to write a guest post about framing and hanging the Camberwell in her house.

I also provided a booklet for her which documented all of the process of planning, designing, and working the piece, so there is a complete “provenance” attached to the piece as well.

The Camberwell Panel – Thirteen

I spent a lot of time in practising stitched Morse Code, in order to arrive at the best way of producing an ornamental but legible effect.

Eventually I settled on this as the best option. The Morse letters are laid out diagonally, using Colonial Knots and Bullion Knots (respectively the dots and the dashes). I discovered that I could mark up the ribbon with the Morse code one word at a time and then stitch over it, making the work slightly less unnerving than if I had had to work it without markings.

My husband wrote a little programme that took the text, converted it to Morse code and then rendered it as a graphic that I could then print out at the appropriate size. That made it possible to mark up the ribbon before I stitched it. I pricked holes – dots and dashes – in the printout, laid it on the ribbon, and marked the ribbon with a quilter’s pencil. A variation of the prick-and-pounce method, I suppose you could say!

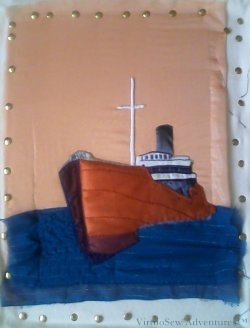

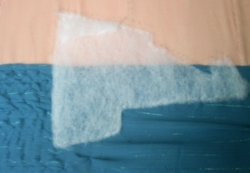

However, before applying the stitched Morse code to the piece itself, I created a padded border using fine wadding and satin ribbon. I wanted to ensure that the edges of the panel did not show through the border, and as it turned out the petersham ribbon was rather fine and showed everything underneath it.

The end is in sight! And even at this point, I have to confess that I was very pleased with the way this was turning out. I hadn’t expected that it would turn out so well with quite so little upset!

The Camberwell Panel – Twelve

There were a few final details to be added to the panel while we discussed the wording of the border, and tracked down suitable materials for working it. These are things like the radio mast and framework beside the superstructure which were worked in a mid-toned, matte grey cotton. The radio mast is in broad chain stitch, which produces a smooth and heavy line, while the framework is in whipped stem stitch which produces a more rounded effect.

Then even more importantly, there was the mooring line. In reality there would be one fore and aft and possibly another amidships, but there is such a thing as too much accuracy!

I tried several ideas, such as crochetted single chain, or even a heavy, single thread, but I finally made the mooring line with mid grey pearl cotton, using a lucet. This is an ancient technique which produces a strong, square braid. It was looped twice around the bollard (which is layered with gauze and padded), and then the free end was whipped to the standing end to simulate the looped cable that would be the first thrown to the quay on mooring. It is only attached at the ends (that is, where it is lead through the scuttle at the bows, and by the bollard about which it is wrapped). That means that it hangs in a fairly natural curve, although it is also both heavy and stiff enough that it has held that curve through the process of framing and transport of the finished article.

Can you tell that my grandfather, too, was a Master Mariner?

The Camberwell Panel – Eleven

At last I could get started on the rigging. I was hoping to get it right as far as it went, although I don’t imagine it is as complex as the real thing. The thread is a medium weight matte cotton thread in a mid toned grey. Essentially each piece of rigging is a single long straight stitch. The connections across the spars are made using a simple figure of eight knot, which interlaces across the spar. This creates the suggestion of a connection, without trying to give great detail.

I used some brown net to represent the shadows on the quayside (railings, I imagine, although the photo doesn’t give that much detail), and stitched another set of catching stitches just inside the quayside edge.

The cotton tape is simply there to give me an approximate idea of where the border is going to go, and thus the true extent of the design.

While I was doing this, I was also thinking – and discussing with my Client – the form that the border would take. We finally settled on a “Dedication” in Morse Code embroidered on to petersham ribbon.

That’s a lot of dots (French Knots) and dashes (Bullion Knots)!

The Camberwell Panel – Ten

I ended up using both fabrics.

I decided to use a layer of the darker fabric to create the shadow of the face of the quayside edge, covered with a layer each of brown and navy net.

The two layers of net intensified the darkness of the shadow, but at the same time, suggested the roughness of the surface. The net was cut as fragments – not the same size – and the heavy material is cut to the same basic shape as the top layer, there were no lines of fabric edges showing through.

The slip for the upper layer was outlined in buttonhole stitch and then attached over the top. At this stage I felt that some additional stitching would be be needed to create an impression of the quayside in similar detail to the ship itself but now the only fabric to be applied was the border.

Which at this point I still hadn’t yet decided on….!

The Camberwell Panel – Nine

When I began to attach the slip, I needed to make sure that the background would be smooth and straight, so as the floor frame was failing to achieve that, I transferred the work to an old set of stretcher bars and used plenty of drawing pins to attach the fabric. I wasn’t concerned about holes in the fabric because the pins were well outside the area of the design that would be on show.

This photo shows the slip of the hull and superstructure, the funnel, and the masts finally attached. Each area was firmly sewn on using a suitable colour of stranded cotton (several different colours in the the case of the hull!), and the holes for the anchor chains were held down to let the background show through.

There are some small elements which yet need to be done on the ship – notably the rigging, but the next important element is the quayside. I had originally picked out two upholstery fabrics to choose between, one of them dark and heavily patterned, and the other lighter and smoother, but as it turned out both of them came in useful….

The Camberwell Panel – Eight

While I was attaching the hull, I was also looking at my references on Stumpwork, or Raised Work. The headache that had been looming all the way through to this point was, How Shall I Do The Mast?

I tried to cover straws with thread or find narrow pieces of plastic or wood, and all of the attempts looked clunky and un-seaman-like. I thought about trying to use stitching – either satin stitch or lines of stem stitching, but in the end decided that these elements needed to be smooth and relatively featureless, whereas the stitching in the piece is entirely to create detail. When I thought a bit harder, it seemed to me that the mast and spar weren’t mere “details” and that there would be a rather jarring effect if I created them using a “detail” technique, rather as though they’d been magnified, or something like that.

In the end I decided to continue using only fabric in the piece. This meant a slightly more difficult process, as the mast and spar are narrow and need to be rounded, but it also maintains the integrity of the design as a purely fabric appliqué.

So: the mast and spar were padded with slivers of felt and covered with narrow cotton tape. This made the ends slightly tricky (the tape kept trying to fray), but provided a clean edge on either side of the spars.

I also attached the padding for the funnel to the background. Both of these needed to be attached before the entire slip for the hull and superstructure were entirely caught down, but at the same time I couldn’t be sure of the placements (wretched shrinkage!) until I had the slip in place.

The Camberwell Panel – Seven

Remember I said that the Camberwell had other ideas for the background?

At this point the deafening racket of complaints from her became too much for me to ignore and I unpicked all of the background and reinstated it, differently. For instance, you might notice that the twinkly fabric for the water is puckered and gathered to create ripples on the surface.

I then pinned on the different choices of quayside fabric I had prepared, and the slip for the hull, and contemplated them for a while. Beside helping to clear up my choice, I realised that the picture was going to work better if I brought the edges in closer to the ship rather than having an expanse of sky above the mast.

So, those choices and decisions made, I moved on. I wanted to make sure that the prow “loomed” somewhat, so I put a layer of padding in the shape of the hull over the background. That should also help to ensure that the horizon line does not show through the slip, as well as differentiating the looming bow from the bridge and superstructure. So I also added a further small extra patch of padding to emphasize the flare of the bow – you can probably just see it.

The Camberwell Panel – Six

I finally decided that I wanted to use two layers of gauze for the sky. The apricot gauze has a slightly reflective surface, which would make the sky glow behind the ship.

I also worked blanket stitch around the outside edge of the panel. At this stage I intended to use a raised band stitch of some sort to frame the work, so the blanket stitch was to form the foundation of the final raised band.

Later I was to discover that the Camberwell herself had Other Ideas, and all of this was completely changed.

I think it is important to show some of the dead ends I investigated here, or at least to describe them. One thing that people who are at the early stages of their creative life always assume is that everyone else gets straight from “Germ of an Idea” to “Finished Design” without really passing through any points in between.

We don’t.

Any of us.

And we are not fair to them – and risk discouraging them – if we allow them to think that we do.

Oops. Rant over!

This next photo shows further progress on the slip for the hull, in which I worked on the superstructure of the bridge and living quarters. I pierced the cotton drill where the anchor chains are lead through the hull and worked one of the portholes on the bridge in a raised satin stitch boss. Almost all the actual embroidery here used ordinary stranded cotton, although sometimes I blended colours in the needle.